A nation founded on slavery—with several centuries of racial injustice toward Native Americans, African Americans and Asian Americans—the United States continues to struggle with its past well into the 21st century.

The National Park Service, a historically white institution, has (had) significant trouble with diversity and attracting people of color to its 400+ sites. Yet, it was the all-Black Buffalo Soldiers who, in the early-1900’s, protected, maintained and literally built the nation’s first national parks.

So, even in America’s national parks, Black and White history are intricately interwoven, more connected than we might realize.

For more background information on African American history, here’s a comprehensive and in-depth timeline of black history in the United States.

Nowadays, there are dozens of National Park Service sites dedicated to African American history and culture.

Contents

- 19 National Park Service Sites That Commemorate African American History

- Jamestown (Colonial National Historical Park), Virginia

- Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Virginia

- Pullman National Historical Park, Illinois

- Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument, Ohio

- Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

- Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

- Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, Alabama

- Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, South Carolina

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park, Georgia

- Booker T. Washington National Monument, Virginia

- Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Alabama

- Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama

- George Washington Carver National Monument, Missouri

- Nicodemus National Historic Site, Kansas

- Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, Maryland

- New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park, Louisiana

- Boston African American National Historic Site, Massachusetts

- Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park, Kansas

- Other African American History National Parks

19 National Park Service Sites That Commemorate African American History

These sites commemorate Black American education and innovation, as well as the civil rights movement and struggle, which is, of course, still ongoing to this very day.

The legacy of many prominent and influential African Americans is preserved at these places, including such iconic figures as Carter G. Woodson, Frederick Douglass, George Washington Carver, Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King, Jr.

From the earliest days of slavery in America to the Underground Railroad, from the Buffalo Soldiers to New Orleans jazz, below you’ll find the best national parks to learn about Black history in America.

This post about national parks commemorating African American history contains affiliate links. You can read more about our Terms of Use / Disclosure here.

Jamestown (Colonial National Historical Park), Virginia

When telling the story of African Americans, it’s important to start at the very beginning. And that story began in 1619 in the Virginia Colony at Jamestown.

In August of that year, the first documented sale of African slaves in British North America occurred at nearby Old Point Comfort—a name that is as ironic as it gets. It involved a group of about twenty Africans from present-day Angola who were sold to the settlers by British pirates flying a Dutch flag.

Initially, Africans were indentured servants in the British North American colony, a system increasingly based on race. Things, however, quickly moved toward what we now consider modern slavery in America: white owners of Black slaves.

By 1662, that form of race-based slavery was widespread in the Virginia Colony and recognized in its statutory law.

The rest, as they say, is history…

You can see a brief overview of the swift progress of institutionalized slavery in 18th-century colonial America on the Historic Jamestowne website.

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Virginia

The Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site in Richmond, Virginia, encompasses the house Maggie Lena Walker lived in for 30 years.

In addition to original artifacts from the Walker family, it also has a great visitor center where you can learn about her life and work, as well as the history of the Jackson Ward community.

Born into a humble family in post-Civil War Richmond, Walker grew up to become one of the greatest community leaders and African American businesswomen of her time.

She devoted her life to the fight for civil rights and the educational and economic empowerment of African American men and women during the Jim Crow era.

Despite suffering from many adversities during her life, Walker became successful in the business and finance world, and was the first African American women to found and serve as president of a bank.

Pullman National Historical Park, Illinois

Also known as the Pullman Historic District, Pullman National Historical Park in Chicago preserves the site of the first model-planned industrial community in the U.S.

The district is a significant historic site because of its origins in the Pullman Car Company, which manufactured railroad cars from the late-19th century to the early-20th century. Notably, this was also the setting of the violent Pullman strike in 1894.

One of the most important African American history national parks, it’s a great place to learn about workers’ rights, civil rights and the history of African American labor in the North.

Created by President Obama as Pullman National Monument in 2015, it was later redesignated as Pullman National Historical Park.

It is the first National Park Service site in Chicago, Illinois, encompassing the Administration Buildings and Pullman Factory, and Hotel Florence.

The A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is named after a prominent African American labor activist and unionist.

In 1925, A. Philip Randolph founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a union of African American laborers. At the time, 44% of Pullman’s workforce were porters, which made Pullman the largest employer of African Americans in the United States.

Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument, Ohio

Situated in rural Wilberforce, Ohio, the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument celebrates the life and achievements of Colonel Charles Young.

Born to enslaved parents in 1864 in Kentucky, Young and his family escaped and relocated to Ohio, where the young Charles showed great interest in music and academics.

He made it into the West Point Military Academy in 1884, eventually becoming the third African American to graduate from that prestigious military school. Throughout his career in the U.S. Army, which was riddled with adversity and racism, his determination, leadership, sense of duty and sheer willpower allowed him to break many ceilings and rose to prominence.

Among his greatest achievements are serving as the first African American military attaché, teaching military history at Wilberforce University, and being the highest ranking Black U.S. Army officer until his death in 1922.

With regards to national parks history, Charles Young has played a critical role, too.

In 1903, he captained a company of Buffalo Soldiers—all-Black regiments of the U.S. Army—in California’s Sequoia and General Grant National Parks (now Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks).

At the time, protection of the young national parks was the job of the U.S. Army, who patrolled parks and performed maintenance work.

As the captain of the Buffalo Soldiers in Sequoia National Park, Charles Young effectively became the very first African American national park superintendent in American history.

Incidentally, the Buffalo Soldiers also were influential in the early days of Yosemite National Park, California

The Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument preserves Young’s home in Wilberforce, Ohio, which he called “Youngsholm.” You can visit the house on guided ranger tours, while a self-guided cell phone tour includes several other, related, sites in Wilberforce.

Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

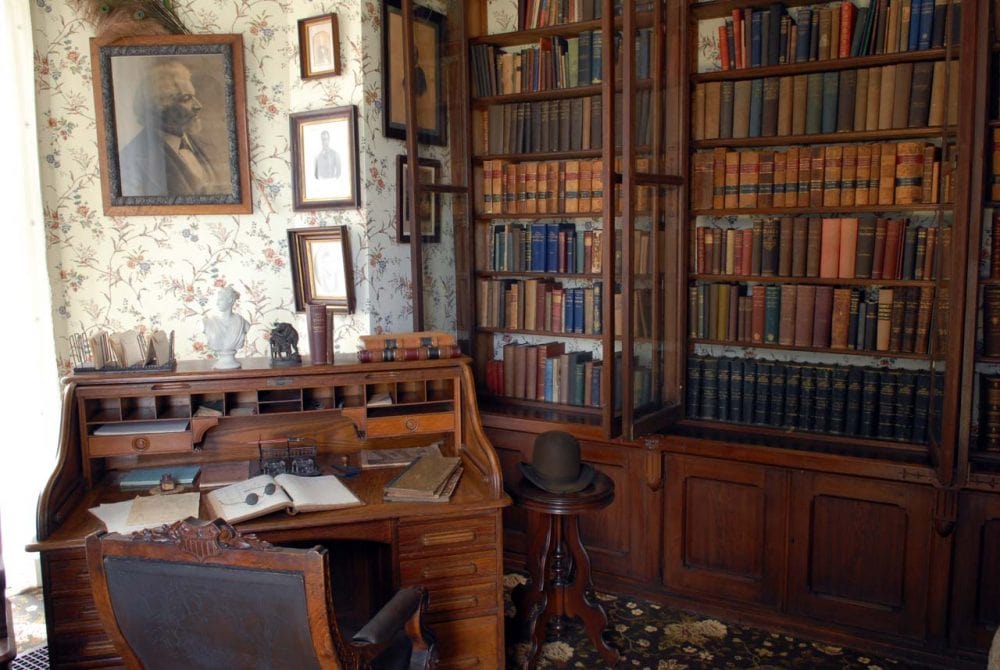

Located at 1538 9th Street NW in Washington, D.C., the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site preserves the home of Carter G. Woodson. This prominent African American author, journalist and historian is known as the “Father of Black History.”

Dr. Woodson lived in this house between 1922 and his death in 1950. His life’s work was documenting the lives and experiences of Americans of African descent, which was virtually non-existent before he dedicated his life to this matter. He became the very first professionally trained historian with African roots in America.

Carter G. Woodson managed the Association for the Study of African American Life and History from this three-story house. Additionally, he also published the Journal of Negro History and Negro History Bulletin while living here.

Most notably, this was the location where Dr. Woodson founded the Negro History Week in 1926. This annual celebration is now known as Black History Month.

This makes the Carter G. Woodson Home one of the absolute best African American history national parks to visit.

Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

Managed together with the Carter G. Woodson Home above, the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site is at 1318 Vermont Ave NW near Logan Circle, Washington, D.C.

This is where Mary McLeod Bethune—a prolific philanthropist, civil rights activist, womanist, humanitarian, writer and educator—established her groundbreaking organization, the National Council of Negro Women, in 1935. Her last home in Washington, D.C., the Council House was the organization’s first headquarters.

From this location, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women created strategies and programs that would benefit the lives of African American women in the United States.

Later on, she founded the Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, Florida. Moreover, Bethune also advised four U.S. presidents on African American affairs and headed the National Youth Administration and the so-called Black Cabinet in the FDR administration.

You can visit the Council House on guided ranger tours on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays.

Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, Alabama

A proclamation signed by President Obama in January 2017 preserved half of the Birmingham Civil Rights District as a national monument.

This was the site of the Birmingham campaign in 1963, known as Project C, with C standing for “confrontation.”

Organized by leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, the campaign aimed to bring attention to civil rights and integration issues in Birmingham, Alabama.

The protest, which involved press conference and staged events, was met with extreme police force and violence. Images of snarling police dogs attacking non-violent protesters and children being hosed with high-pressure water made their way around the globe, sparking more protests.

At Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, the clash between civil rights activists and segregationists is especially clearly illustrated by places like the A.G. Gaston Motel.

A center of the civil rights movement and the place were Project C activities were planned, this Black-owned motel was bombed in the night of May 11, 1963.

The violent suppression of these peaceful protests by both the police and white southerners resulted in nationwide public outrage. Eventually, these events helped pass the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Major landmarks around the A.G. Gaston Motel include the following:

- Kelly Ingram Park – the site of the violent police response, with dogs and water cannons, to peaceful protesters.

- 16th Street Baptist Church – where four young girls were killed by a bomb in September 1963.

- 4th Avenue Historic District sites – a center of Black-owned businesses during the period of forced segregation in Birmingham.

- Birmingham Civil Rights Institute – educational and cultural research center with exhibits showcasing the civil rights struggle in Birmingham.

Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, South Carolina

“A forgotten founder”, Charles Pinckney contributed to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution, was governor of South Carolina and minister to Spain in the Thomas Jefferson administration.

Pinckney inherited his father’s Snee Farm plantation just outside of Charleston in 1782. It was both a country retreat and a working indigo and rice plantation with a large workforce of hundreds of Black slaves.

At this national historic site, exhibits and buildings interpret the life of Charles Pinckney, as well as the lives of the free and enslaved residents of the former plantation.

It is an essential place to visit for anyone who wants to learn more about the era of slavery in the American South.

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

Preserving the home and estate of Frederick Douglass, the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site commemorates the life and legacy of one of the most prominent black Americans of the 19th century.

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in 1818, escaped as a young adult and went on to become one of the strongest voices in the abolitionist movement.

His inclusive vision of humanity, determination during times of struggle, and inspiring words continue to influence people to this day.

Douglass spent the last seventeen years of his life at this house (between 1877 and 1895), which he named Cedar Hill. The national historic site’s centerpiece is the house itself, perched atop a 50-foot hill and offering great views of downtown Washington, D.C.

It has been restored to the way it looked in 1895, furnished with original objects and artifacts that belonged to Frederick Douglass himself, as well as his family members. You can see the house only on guided ranger tours, while the grounds are open for self-guided exploration.

Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park, Georgia

Easily one of the most influential people in the history of the United States, Martin Luther King, Jr. represents an important chapter in America’s civil rights story.

His vision, oratory skills and powerful voice that reverberates through time have shaped—and continue to shape—the future of the country.

If you’d like to learn more about Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life and legacy, there’s no better place than the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical in Atlanta, Georgia. This is one of the greatest and most significant African American history national parks.

Made up of dozens of historic buildings and sites, this is where you can walk in Dr. King’s footsteps and follow him on his civil rights journey. The park preserves the places where he was born and where he lived, worshiped and worked.

The natural starting point of a visit to Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park is the Visitor Center, which has great exhibits on Dr. King’s life and the civil rights movement. Other major landmarks include:

- Martin Luther King, Jr. Birth Home – Two-story birth home of Martin Luther King, Jr. (born as Michael Jr.).

- Fire Station No. 6 – Built in 1894, this historic fire station served the Auburn community until 1991. It has exhibits about the desegregation in the Atlanta Fire Department.

- Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church – Place where Martin Luther King, Jr. was baptized, ordained as a minister, and was a pastor until his death in 1968.

- Behold Monument – Sculpture that commemorates the principles and morals of Martin Luther King, Jr.

- “I Have a Dream” World Peace Rose Garden – Situated next to the Peace Plaza at the Visitor Center, the World Peace Rose Garden is an artistic representation of Dr. King’s life and ideals of peace through non-violence.

- The King Center – Located across the street from the Visitor Center, the King Center is the final resting place of Dr. and Mrs. King. There are exhibits on Martin Luther King, Jr. and his wife, as well as Mahatma Gandhi.

You can also learn more about Dr. King’s life and legacy at the famous Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. This large and iconic sculpture stands in West Potomac Park, just south of the Lincoln Memorial at the National Mall.

Booker T. Washington National Monument, Virginia

Born a slave in 1856 on a tobacco town in Franklin County, Virginia, Booker T. Washington would go on to found and become the first principal of the Tuskegee Institute (see below) in 1881.

Later on in his life, his work as a public speaker, author, educator and advisor would make him one of the most influential African American men of his era.

The Booker T. Washington National Monument preserves the place where Washington was born into slavery.

Exhibits showcase the lives of slaves on a farm in mid-19th-century Virginia, while also focusing on the life and achievements of Booker T. Washington himself. Additionally, there are short hiking trails, a picnic area, and farm and garden areas.

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Alabama

The “Tuskegee Airmen” were participants in a 1940’s U.S. Army Air Corps experiment, known as the “Tuskegee Experiment.” The purpose of this experiment was to determine whether or not African Americans were mentally and physically capable of learning how to operate and fly an aircraft.

Although it was still a clear example of blatant racism, the Tuskegee Experiment of 1941 was, in fact, the first time in American history an all-African American flight squadron was created. Before 1940, African Americans weren’t allowed to fly in the Army at all.

The Tuskegee Airbase was the only flight training facility for African American pilots in World War II.

It’s important to note that the Tuskegee Airmen not only included African Americans, but also some Native Americans, Latinos, Caribbean Islanders and mixed-race people.

Additionally, there were quite a lot of Black women involved, too, who worked alongside the men as control tower operators, secretaries, aircraft technicians and parachute trainers.

The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site is located at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama. It preserves the training base, which was built in 1941, and contains the Hangar #1 and Hangar #2 Museums, as well as numerous wayside exhibits.

You can read about why the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site remains a significant place to this day here.

Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Alabama

The Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site is another African American history park in Tuskegee, Alabama.

When Booker T. Washington (see above) arrived in Alabama in 1881, he began building the Tuskegee Institute, “both in reputation and literally brick by brick.”

The school opened on July 4, 1881 and quickly became an iconic African American educational institute.

Having become the school’s first principal when he was only 26 years old, Washington hired the best and brightest people he could find. This included Robert Taylor and George Washington Carver (see below), who arrived in Tuskegee in 1896.

Carver would go on and become a renowned agricultural scientist and inventor, known for his work with and on peanuts, as well as research on crop rotation.

The national historic site preserves many original buildings of what is now the Historic Campus District of Tuskegee University, which were constructed by the students themselves with bricks made in the institute’s own brickyard.

George Washington Carver National Monument, Missouri

Established in 1943 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the George Washington Carver National Monument was America’s first national monument dedicated to an African American. It was also the first one to honor someone other than a U.S. president.

Located in the southwestern corner of Missouri, the monument preserves George Washington Carver’s birthplace and boyhood home, which was a farm with slaves.

The visitor center has exhibits on science and history, a museum, classrooms with programs about Carver’s life, and a 26-minute-long film.

Outside, you can walk the 1-mile self-guided Carver Trail, where you can see several historic sites, including George Washington Carver’s birth site, the Boy Carver Statue, the 1881 Moses Carver House and the graves of Moses and Susan Garver (who were the slave-owning farmers).

Carver’s lifelong passion for learning eventually brought him to Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute (see above). There, he headed the school’s Agriculture Department, teaching for 47 years.

He became an authority on agriculture in America, famous for his research on crop rotation and farming techniques, and received numerous honors for his work.

Calling him the greatest African American scientist of the early-20th century is not an exaggeration. Additionally, Carver also was a great humanitarian and environmentalist.

Although he’s known as the “Plant Doctor” or “Peanut Man”, his life encompassed so much more. You can learn all about it at the fascinating George Washington Carver National Monument.

Nicodemus National Historic Site, Kansas

During the Reconstruction Period in post-Civil War America, many previously enslaved African Americans moved west from Kentucky into Kansas. Often completely ignored in the history of the American West, Black Americans actually played a significant role in the settling of the Great Plains.

Nowhere is this so evident as at Nicodemus National Historic Site in Kansas. This unique National Park Service site preserves the oldest and only remaining African American-founded town west of the Mississippi River.

The site encompasses five different historic buildings, representing the five key pillars of life at Nicodemus:

- Old First Baptist Church – Religion

- African Methodist Episcopal Church – Religion

- School District Number 1 – Education

- The Township Hall – Self-government

- St. Francis Hotel / Switzer Residence – Family life and business

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, Maryland

Born into slavery in Maryland in 1822, Harriet Tubman escaped when her enslaver died and she was put up for sale. She was 27 years old at that time, vowing to return to Maryland and rescue her friends and family.

During the next ten years, she made 13 trips back to Maryland, risking her own life to free others.

Arguably her most famous accomplishment is giving instructions to 70 slaves so they could find freedom in the North. She applied the skills she’d learned while working in the fields, forests and wharves during her many escapes and to expand her network of collaborators.

Harriet Tubman was one of the most famous “conductors” on the Underground Railroad. She claimed she “never lost a passenger.”

Tubman became one of the most influential abolitionists and civil rights activists of her time, befriending other humanitarians and intellectuals such as Frederick Douglass, John Brown, Lucretia Coffin Mott and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Maryland has a visitor center where you can learn more about Tubman’s life and work. There are exhibits, an educational film and picnic areas.

Additionally, the visitor center is also the orientation center and starting point of the fascinating Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Scenic Byway.

After her escape from slavery in Maryland, Tubman eventually settled in central New York State, a hub of abolitionism, women’s suffrage and progressive thought. There, she continued her fight for human rights until her death in 1913. You can explore the place where she spend much of her free life at the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in upstate New York.

New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park, Louisiana

Modern American culture wouldn’t exist without African American creativity, innovation, determination, passion and entrepreneurship. Arguably the best example of that is music.

From blues and jazz to hip-hop, Black music and culture have transformed, shaped and influenced American society for decades, if not centuries.

To learn more about the history of jazz, there’s no better place than the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park.

Located near the city’s famous French Quarter, the park features exhibits on the origins and evolution of jazz, photos and multimedia, ranger tours and, of course, jazz concerts.

Boston African American National Historic Site, Massachusetts

Situated on the North Slope of Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood, the Boston African American National Historic Site encompasses 350 years of history.

The site preserves several historic buildings dating from before the Civil War related to the African American community in early-19th-century Boston. All these structures are linked by the Black Heritage Trail®, a 1.6-mile walk through this history-packed neighborhood.

Although most individual sites along the trail are private houses, a number of them are open to the public.

Especially the Abiel Smith School and the African Meeting House, the oldest still standing Black church in the United States, are worth visiting. Both are part of Boston’s Museum of African American History.

All these buildings have played a significant role in the story of African Americans—in Boston and the United States as a whole.

From the George Middleton House (leader of a local Black militia during the American Revolution) to the Phillips School (which became one of Boston’s first integrated schools in 1855) to the Lewis and Harriet Hayden House (an Underground Railroad safe house), the sheer amount of history preserved by the Boston African American National History Site is phenomenal.

Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park, Kansas

Arguably one of the most important Supreme Court rulings regarding African American rights involved a Black school in Topeka, Kansas.

The Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park commemorates the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous decision to end racial segregation in public schools on May 17, 1954.

It ruled that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal”, a violation of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

While this was a landmark case, changing public education in America forever, the people involved were ordinary people. As the National Park Service says, “they were teachers, secretaries, welders, ministers and students who simply wanted to be treated equally.”

The historic site comprises of the Monroe Elementary School and its grounds, which was one of Topeka’s four segregated schools before the Oliver L. Brown et al. v. the Board of Education of Topeka et al. case.

It has an auditorium showing the 30-minute movie Race and the American Creed, a couple of exhibit galleries and a bookstore.

Additionally, the Monroe school’s former kindergarten room has been restored to its 1954 appearance and is open to the public.

Other African American History National Parks

In addition to the national parks commemorating African American history featured above, there are several more sites where you can learn about civil rights, people and/or historic events:

- African American Civil War Memorial, Washington, D.C.

- African Burial Ground National Monument, New York

- Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, Alabama

- Freedom Riders National Monument, Alabama

- Reconstruction Era National Historical Park, South Carolina