How the Trump Administration’s 2026 Budget Request Could Affect National Parks

The Trump administration’s Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Request, which was published on May 2, 2025, contains countless cuts to numerous government departments, agencies, services, and programs. This includes the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the National Park Service (NPS).

Specifically, the document calls for a massive $900 million cut to the budget for the “Operation of the National Park System,” along with a number of other cuts affecting the National Park Service.

If approved by Congress, it would be the largest budget cut in the 109-year history of the Park Service.

At the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), President and CEO Theresa Pierno called it “the most extreme, unrealistic and destructive National Park Service budget a President has ever proposed in the agency’s 109-year history. It’s nothing less than an all-out assault on America’s national parks.”

The description in the FY 2026 Budget Request that goes with those unprecedented budget cuts is as follows:

“The National Park Service (NPS) responsibilities include a large number of sites that are not “National Parks,” in the traditionally understood sense, many of which receive small numbers of mostly local visitors, and are better categorized and managed as State-level parks. The Budget would continue supporting many national treasures, but there is an urgent need to streamline staffing and transfer certain properties to State-level management to ensure the long-term health and sustainment of the National Park system.”

There are a few different things going on in that statement, so let’s break it down. Let’s take a facts-based look at what this would actually mean to the National Park System.

In order to do that, I downloaded federal funding, visitation, and economic impact reports from the NPS and compiled all the data in one sprawling spreadsheet.

In total, I ended up with 339 NPS units that have reliable data on funding, visitation and economic impact. The data dates from 2023, which is the latest year for which those statistics have been published by the federal government (in the National Park Service’s Visitor Spending Effects Report and the Interior Department’s FY 2025 Budget Justification).

It’s also worth noting that several of those 339 “units” are consolidated units, meaning that they consist of two or more individual units that are funded and managed collectively. So, those 339 units actually represent many more individual units.

Additionally, I should mention that a number of NPS units do not collect or report these statistics and are, as such, excluded from the overview.

What Would a $900 Million Cut to National Park System Operations Mean?

One of my earliest and, to be honest, most striking conclusions was that many National Park Service units actually don’t get all that much federal funding. Approximately half of those 339 units (163 to be precise) receive less than $2 million of federal funding per year.

So what would have to happen to cut $900 million from the “Operations of the National Park System” budget?

Ranked By Federal Funding

Let’s look at the lowest-funded NPS units and add up their annual federal funding until we get to $900 million.

How many park budgets would have to be eliminated to end up with $900 million of “savings?”

Based on the Interior Department’s own FY 2025 Budget Justification report, a total of no fewer than 310 of the lowest-funded NPS units would have to lose their annual funding to get to $900 million.

Shockingly, this would include iconic parks like Acadia, Death Valley, Dry Tortugas, Badlands, Crater Lake, Arches, and Joshua Tree, as well as units with other designations, such as Pearl Harbor, Santa Monica Mountains, Chaco Culture, and even Mount Rushmore.

Put differently, out of those 339 park units that have comprehensive data available, only 29 would survive these cuts.

Considering that some of those units are actually groups of individual parks, the grand total of individual park budgets to be eliminated is actually closer to 350.

This was reported earlier by the National Parks Conservation Association and National Parks Traveler, and my own calculations—which, again, are based on official federal government data—back this up.

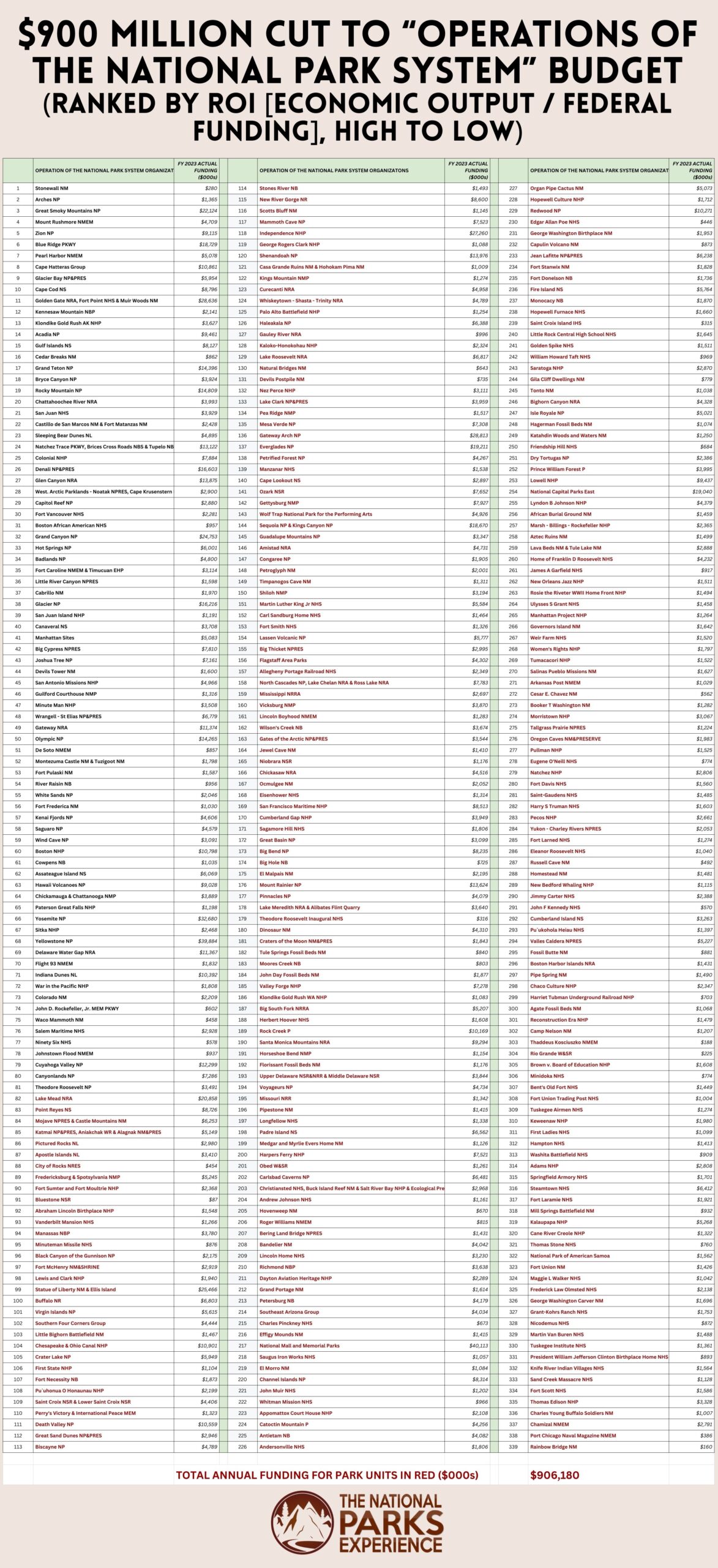

Ranked By Economic ROI

Of course, there are many ways to get to $900 million in budget cuts. So, let’s try a different way.

Let’s sort all the park units by ROI (which is their annual economic output divided by their annual federal funding) and see which of the lowest-ROI parks will need to lose their funding.

With this approach, we’d actually be able to keep more park units and get to that proposed $900 million. This would eliminate the budgets of the least “profitable” park units.

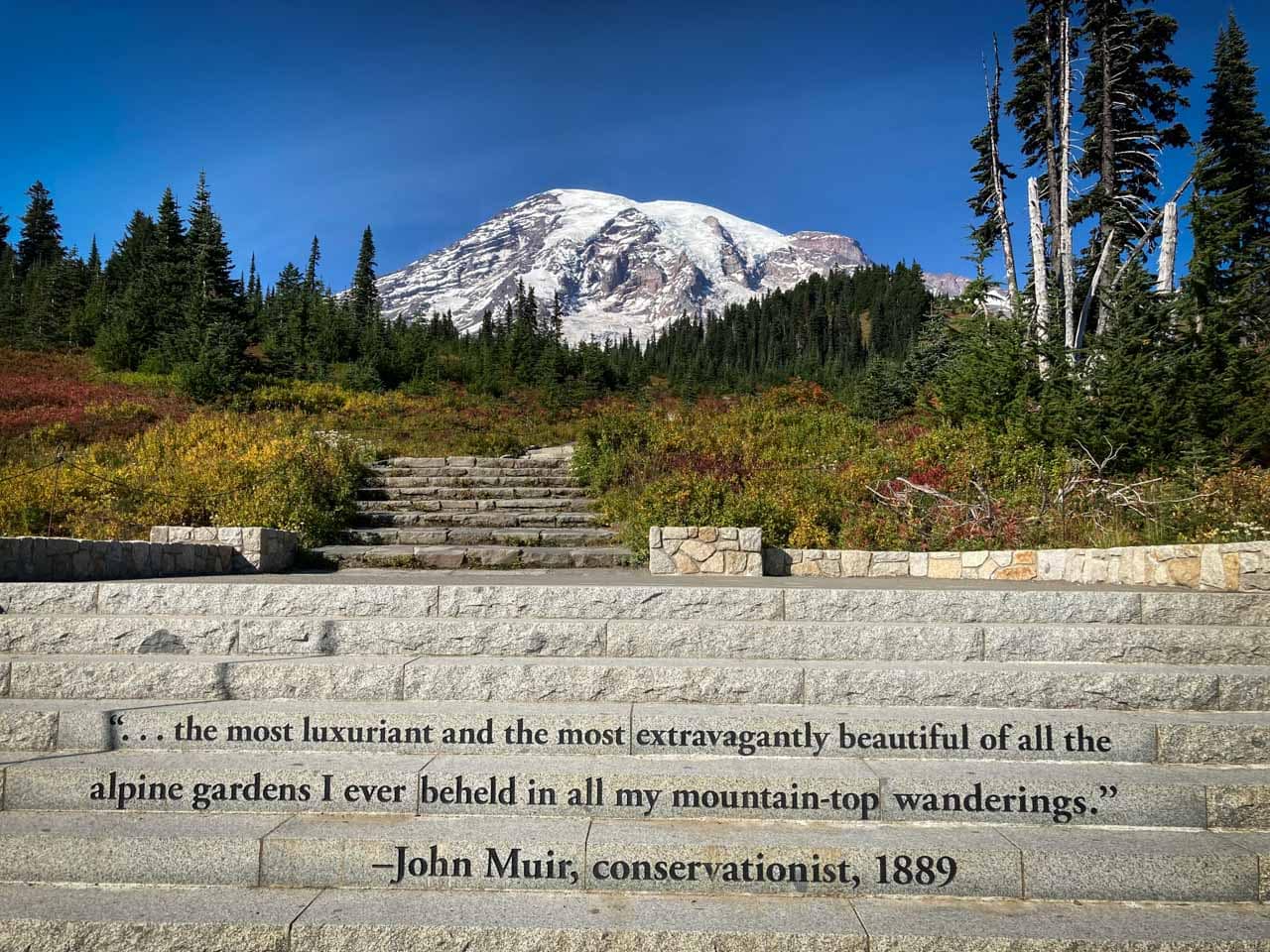

However, believe it or not, that would include eliminating the entire budget of—effectively abolishing—parks like Lake Mead, Great Sand Dunes, Shenandoah, Everglades, the North Cascades parks complex, Mount Rainier, Mesa Verde, and even all National Mall and Memorial Parks. These are just a handful of high-profile examples.

This approach would still require the complete defunding of 258 park units, which, as specified above, is actually closer to 300 individual units because several of them are managed collectively.

CONCLUSION: As these indisputable facts show, it is completely unrealistic—impossible even—to cut $900 million from the “Operations of the National Park System” budget and not entirely decimate the entire park system. The math is right there and numbers don’t lie.

“The president’s proposed budget plan is beyond extreme. It is catastrophic. If enacted by Congress, our national park system would be completely decimated.”

– Theresa Pierno, President and CEO of the NPCA

What Are National Parks in the “Traditionally Understood Sense?”

“The National Park Service (NPS) responsibilities include a large number of sites that are not ‘National Parks,’ in the traditionally understood sense,” the description in the FY 2026 Budget Request says.

So, this begs the question: what does the “traditionally understood sense” actually mean.

Is it the definition of a national park when Yellowstone was established in 1872, or when the National Park Service was created in 1916? Or maybe another definition that was established later on?

Nothing is clearer on what the purpose of a “national park” is than the text of the Organic Act of 1916, which created the National Park Service itself. It specifies the mission of the National Park Service as follows:

“The service thus established shall promote and regulate the use of the Federal areas known as national parks, monuments, and reservations hereinafter specified by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purposes of the said parks, monuments, and reservations, which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Note that it specifically mentions scenery, natural and historic objects, and wildlife.

This means that there’s a wide range of places that could be eligible for management by the National Park Service. This includes landscapes and ecosystems, but also “historic objects,” which may include everything from Native American archaeological sites to battlefields, monuments and memorials, historic homes and neighborhoods, and architectural landmarks.

Therefore, the text by which the National Park Service was established doesn’t put any limitations on what can or cannot be a “park” managed by the NPS.

And indeed, as history has shown, the park system has grown into a wide-ranging collection of all kinds of parks of national significance. Together, they offer a comprehensive overview of American history, culture, and nature. The National Park System is America.

Let’s also take a look at the mission statement of the National Park Service, which shreds all possible doubt about the limitations of what a “national park” is or could be:

“The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. The National Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world.”

Note the words “natural and cultural resource conservation.” This, again, confirms that a NPS-managed park could just as easily be a mountainscape as a historic home or archaeological site.

CONCLUSION: The “traditionally understood sense” of what a national park is, is outlined in the Organic Act of 1916. It says that the purpose of a park is “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein.” This broad definition leaves room for a wide variety of places to be included in the National Park Service system, from unique landscapes and vulnerable wildlife habitats to buildings, bridges, monuments, memorials, and places of innovation and invention.

“Our national parks aren’t just places on a map. They’re our shared legacy, safeguarding the beauty, history and culture of our country. For over a century, Americans have loved and protected our national parks, battlefields, historic sites, recreation areas and so much more. We can’t be the generation that lets an administration’s reckless agenda unravel this great legacy. Silence is complicity. Congress must get off the sidelines and act now. Every member of Congress must stand up and reject this reckless proposal.”

– Theresa Pierno, President and CEO of the NPCA

Do Many Sites Actually Receive Mostly Local Visitors?

Let’s zoom in on another specific part of the FY 2026 Budget Request’s description above. Let’s verify if it’s true that many national parks “receive small numbers of mostly local visitors,” which is mentioned as a reason why they would be better categorized and managed as state-level parks.

How many NPS units do, in fact, receive mostly local visitors?

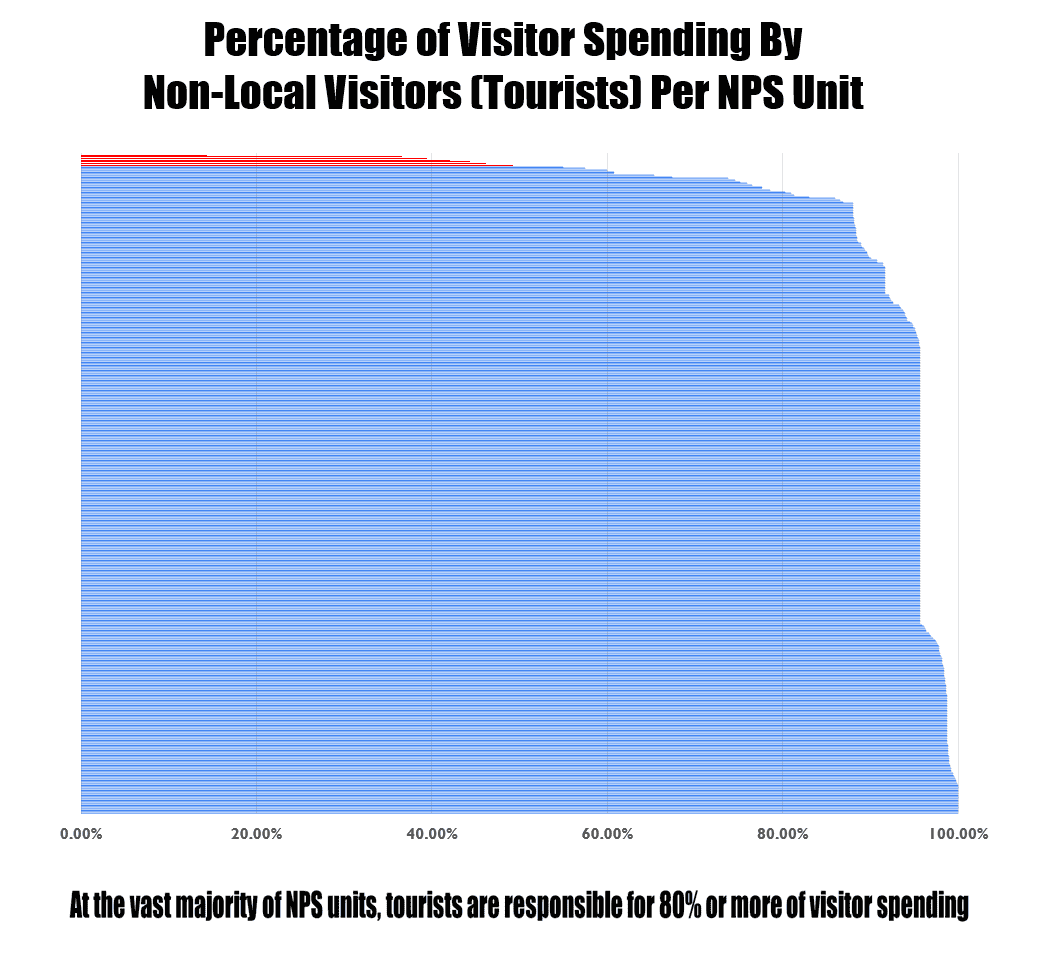

Well luckily, we have the National Park Service’s own Visitor Spending Effects report to rely on, which specifies the exact “Percent Visitor Spending from Non-Local Visitors.”

Put simply, this is the percentage of total visitor spending at and near a park unit by tourists.

While this doesn’t directly show how many park visitors are non-locals, this data does provide a valuable insight into how much the regional economy of a specific NPS unit relies on tourists in economic terms.

The Visitor Spending Effect report shows that, out of the 396 NPS units that track those stats, 389 generated more visitor spending from tourists than from locals in 2023.

That means that there are only seven (7) park units that rely more on local visitors than on tourists. Seven!

They are:

- Lake Meredith NRA (14.3% visitor spending by tourists)

- Catoctin Mountain Park (36.6%)

- National Capital Parks East (39.4%)

- Greenbelt Park (42.0%)

- Minidoka NHS in Idaho (44.3%)

- Valley Forge NHP (46.2%)

- Prince William Forest Park (49.2%)

The chart below shows a visual overview of those 396 NPS units that have visitation data available.

The red lines at the top are the seven units where locals spend more money than tourists. All the others, the blue lines, are units that generate more spending by tourists than by locals.

The vast majority of park units rely almost entirely on non-local visitation (also known as tourism), with no fewer than 374 park units where tourist spending is responsible for more than 80% of the total dollars spent by visitors.

Below, you can see the complete list of all available NPS units and their percentage of tourist spending.

Therefore, the claim that many national parks “receive small numbers of mostly local visitors” is hereby thoroughly debunked, by the federal government’s own statistics.

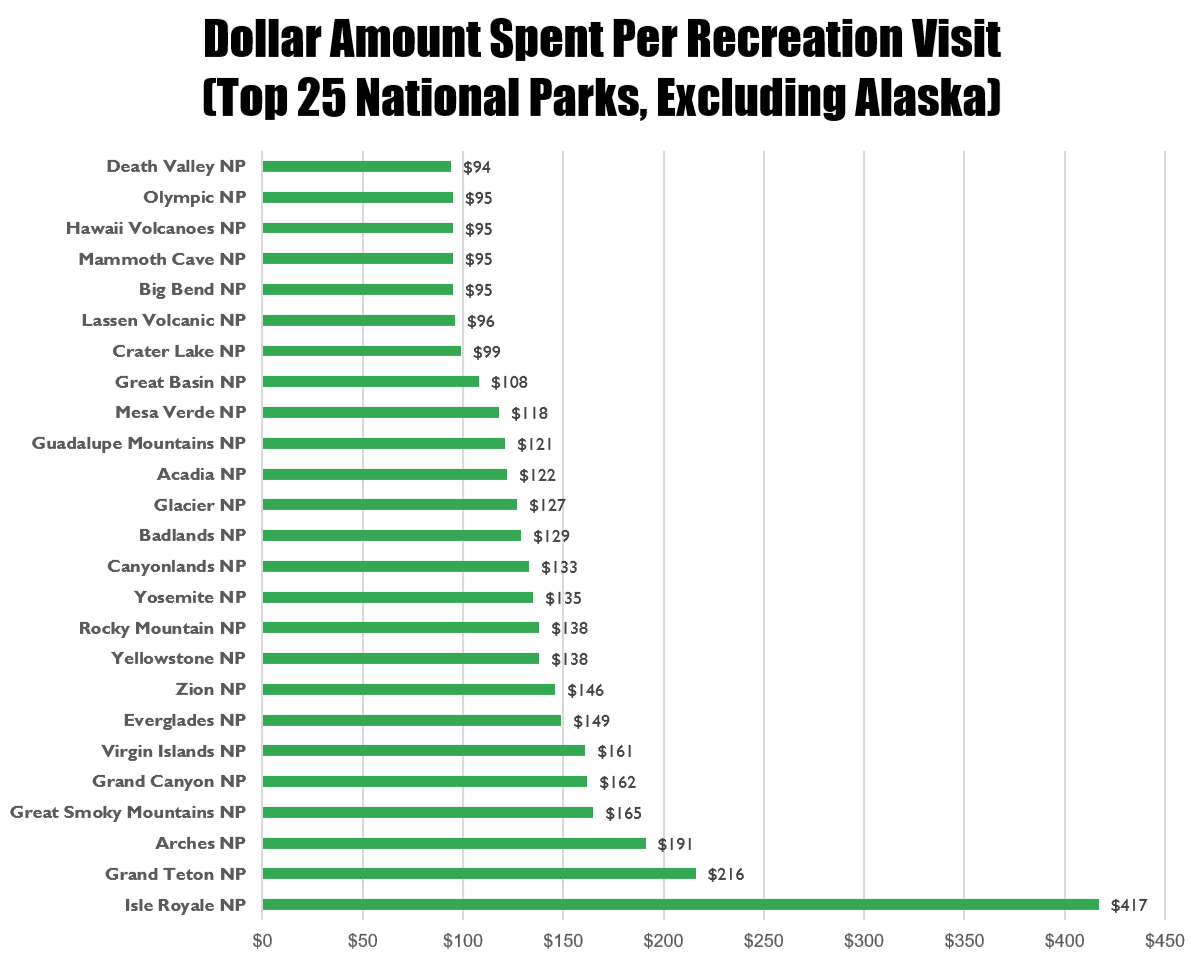

How Much Do Park Visitors Spend?

On average, across the National Park System, park visitors, including both locals and tourists, spend $113 per recreation visit.

This dollar amount spent per recreation visit varies greatly, though, from $3 per visit to the National Mall and Memorial Parks in Washington, D.C. (many of which are free anyway) to $2,238 per visit to the remote Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve in Alaska (which is very difficult and expensive to get to).

Here is the top 25 of national parks (outside of Alaska) where visitors spend the most money per recreation visit.

CONCLUSION: National parks are extremely popular tourist destinations, with local economies that depend enormously on the millions of dollars those tourists bring in. On average, each recreation visit to a NPS unit results in $113 of visitor spending, most of which is by non-local visitors.

“Abandoning our national parks like this would be disastrous. Many states don’t have the resources to maintain these parks and the federal government walking away from their responsibility would result in closed parks, safety risks, trails that are not maintained, and far fewer park rangers. This will be disastrous for not just visitors and resources, but local economies who depend on park tourism as economic drivers. Congress should reject this proposal outright.”

– Emily Thompson, Executive Director of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks

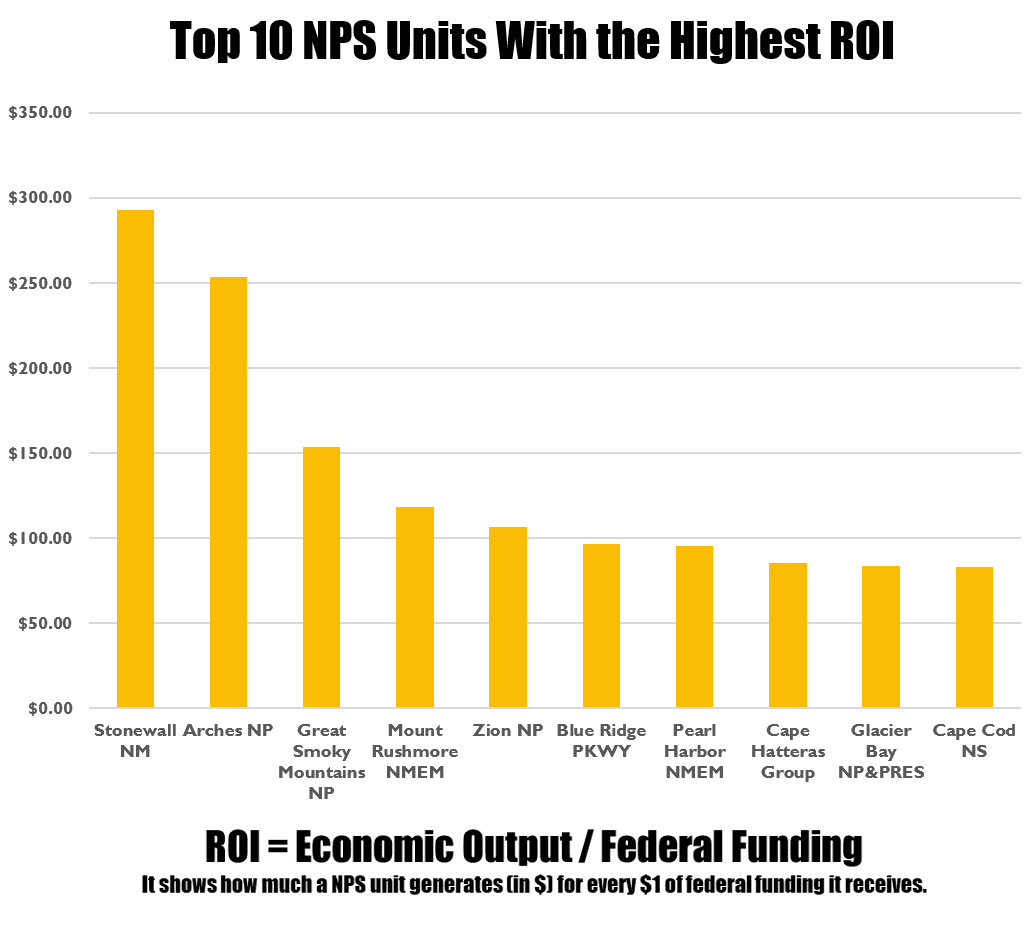

What’s the ROI of National Parks?

America’s system of national parks is a money-making powerhouse. Even though it’s not intended to generate revenue, the simple fact that it does is another reason why it’s worth continuing to fund it properly.

Once again, the numbers tell you everything you need to know.

The annual NPS budget is approximately $3.5 billion. (That’s merely 0.067% of the entire annual federal budget.)

However, visitor spending across the park system resulted in a record-high $55.6 benefit to the U.S. economy in 2023. This is known as “economic output,” which is the sum of business-to-business sales, exports, and sales to consumers supported by visitor spending.

Simply put, for every $1 of federal funding the National Park Service receives, the parks generate $15 in economic output. That’s an incredible return-on-investment.

When looking at individual NPS units, out of the 339 units that have data on both funding and economic output, there are no fewer than 312 that contribute more to the economy than they receive in federal funding.

Let’s take a look at the top ten park units with the highest ROI.

- Stonewall National Monument ($292.63 of economic output for every $1 of federal funding)

- Arches National Park ($253.36)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park ($153.58)

- Mount Rushmore National Memorial ($118.22)

- Zion National Park ($106.12)

- Blue Ridge Parkway ($96.66)

- Pearl Harbor National Memorial ($95.13)

- Cape Hatteras Group ($85.23)

- Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve ($83.72)

- Cape Cod National Seashore ($83.01)

CONCLUSION: As a whole, the National Park System is a massive economic powerhouse. With an annual budget of $3.5 billion, it contributes more than $55 billion to the U.S. economy per year. Put another way, for every $1 of federal funding, the parks generate $15 for the economy.

Are There Any Park Units That Generate Less Than What They Receive in Funding?

Yes, in 2023, there were 27 NPS units that generated less economic output than the federal funding they received:

- Rainbow Bridge National Monument

- Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial

- Chamizal National Memorial

- Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument

- Thomas Edison National Historical Park

- Fort Scott National Historic Site

- Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

- Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

- President William Jefferson Clinton Birthplace Home National Historic Site

- Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site

- Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

- Nicodemus National Historic Site

- Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site

- George Washington Carver National Monument

- Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

- Maggie L Walker National Historic Site

- Fort Union National Monument

- National Park of American Samoa

- Thomas Stone National Historic Site

- Cane River Creole National Historical Park

- Kalaupapa National Historical Park

- Mill Springs Battlefield National Monument

- Fort Laramie National Historic Site

- Steamtown National Historic Site

- Springfield Armory National Historic Site

- Adams National Historical Park

- Washita Battlefield National Historic Site

While, strictly economically speaking, they could be considered “unprofitable” or “losing money,” it’s worth remembering that the National Park System, let alone its individual units, is not supposed to directly generate revenue.

As I mentioned above, its purpose is to “…conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Additionally, It goes without saying that, even if these parks cost more than they generate, they still preserve or commemorate important places/events/people in U.S. history and culture, which aligns completely with the mission of the National Park Service.

After all, not everything is about economic value. Things like emotional value, spiritual value, historical value, and cultural value are real, too, and arguably even more important than mere money.

CONCLUSION: From historical figures like Charles Young, Martin Van Buren, George Washington Carver, Thomas Edison and Frederick Law Olmsted to important historical locations such as Knife Indian Villages, Fort Laramie, Tuskegee Institute, and Sand Creek, these NPS units are a crucial part of the American story. Although they may costs more than they contribute to the economy, these parks are incredibly valuable in other ways and deserve continued protection.

“America has changed dramatically since the birth of the National Park Service in 1916. The agency’s roots lie in the parks’ majestic, often isolated natural wonders and in places that exemplify our cultural heritage, but our reach now extends to places difficult to imagine 100 years ago — urban centers, rural landscapes, deep oceans, and night skies.”

– Jonathan B. Jarvis, former Director of the National Park Service

Have National Parks Ever Been Transferred to the States or Abolished?

Transferring National Park Service units to the states, to other federal agencies, or abolishing or delisting them altogether is not unprecedented. It has happened multiple times in the past 150 years or so.

Examples of national parks and monuments that no longer exist include the following:

- Father Millet Cross National Monument: Established in 1925, but transferred to the state of New York in 1949 where it’s now part of the Old Fort Niagara State Historic Site.

- Mackinac National Park, Michigan: Established in 1875 (as the second national park in the United States, just three years after Yellowstone), but abolished in 1895 and transferred to the state of Michigan where it became, and still is, Mackinac Island State Park.

- Lewis and Clark Caverns National Monument, Montana: Established in 1908, but transferred to the state of Montana in 1937 because it was too costly to operate, became Montana’s very first state park.

- Sullys Hill National Park, North Dakota: Established in 1904, but delisted in 1931 and repurposed as a game reserve, now known as White Horse Hill National Game Preserve.

- Wheeler National Monument, Colorado: Established in 1933, but due to lack of proper road access and declining visitation was transferred to the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) in 1950, now part of Rio Grande National Forest.

- Shoshone Cavern National Monument, Wyoming: Established in 1909, but abolished in 1954 and transferred to the city of Cody, Wyoming. Managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) since 1977.

- Papago Saguaro National Monument, Arizona: Established in 1914, but lack of funding and proper management forced it to be transferred to the state of Arizona where it’s now a large municipal park in Phoenix, called Papago Park.

- Old Kasaan National Monument, Alaska: Established in 1916, but abolished in 1955 and transferred to the U.S. Forest Service, which now manages it as part of Tongass National Forest.

- Platt National Park, Oklahoma: Established in 1906, but abolished in 1976 and included in Chickasaw National Recreation Area, which is still managed by the National Park Service.

There are many reasons why NPS units have been transferred to state or local governments, or incorporated into other federal lands or parks. Common reasons have been lack of funding or visitor interest, questionable national significance, mismanagement, and inaccessibility.

CONCLUSION: There most certainly is precedent to transferring NPS units to states and local governments, or incorporating them into other existing federally managed lands. However, it’s important to know that all previous transfers, delistings, or abolitions were done by acts of the U.S. Congress—this is not within the power of any U.S. President.

Sources

- National Park Service 2023 Visitor Spending Effects Report

- Department of the Interior FY 2025 Budget Justification

- White House FY 2026 Budget Request

- National Parks Index

What You Can Do To Help Protect National Parks

If you care about our national parks and public lands, their dedicated employees, their wildlife, and the peril they find themselves in at the moment, there are a few things you can do to help.

The first, and arguably most important, action you can take is letting Congress know how seriously this is affecting hard-working, genuine, passionate, and qualified Americans—on both sides of the political aisle.

You can conveniently do that by filling out one of these forms on the National Parks Conservation Association website.

Additionally, you can also contact your Senator or Representative directly. The best way to do that is through the 5 Calls app.

Other ways to help is by donating to conservation associations like the abovementioned National Parks Conservation Association, the National Park Foundation, or the National Forest Foundation.

In a more practical way, when visiting national parks and forests, always make sure to follow the seven Leave No Trace Principles. This is more important than ever, considering that public lands may have fewer staff available. Keep yourself safe, keep the landscape clean, leave the wildlife alone, be nice to park rangers, stay on trails, and look out for other visitors as well.